September 22, 2000

Would Repeal of Trade Sanctions Solve Crop Agriculture’s Price and Income Problems

For a number of years the U.S. has imposed unilateral trade sanctions on Cuba, Iran, Iraq, Sudan, Libya and North Korea. Naturally, American farmers wonder just how much of agriculture’s current price and income distress is due to missed export opportunities in those countries.

Farmers have long called for repeal of the sanctions, but they became particularly vocal about removing sanctions after the passage of the last farm bill. If American farmers are expected to operate in a freer market, our producers argue, it is unfair for the U.S. government to shut off certain markets due to political considerations. I find that argument very convincing.

In fact, when the 1996 Farm Bill was passed, the package as presented to farmers included: 1) expansion of exports through aggressive trade policies, especially the lifting of unilateral trade sanctions, 2) reduced taxes and 3) less regulation. Some have suggested that if these additional actions had been taken, crop agriculture would not be depressed as it is now. Rather, it would be able to thrive in the freer market economy envisioned in the 1996 Farm Bill.

Of the various actions, the opening up of new crop export markets through repeal of trade sanctions would seem to be one of the better candidates for making agriculture financially healthy under the original provisions of the 1996 Farm Bill, i.e., with no dispersal of emergency payments. By themselves, tax reductions and fewer regulations would provide little financial relief for crop agriculture. No reduction in tax rates or lower tax obligations, for example, could offset the sharp reductions in crop prices and market-generated net income of the last three years. And, although environmental and other regulations can significantly increase the cost of producing livestock, major agricultural crops are subjected to relatively few cost-increasing regulations, especially when compared to the production of most non-agricultural products.

Okay. So let’s suppose the sanctions had been lifted in, say, 1996. What would have been the impact on crop prices and agriculture’s ability to prosper without emergency payments over the last four years? We, at the Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, began an analysis of this question by first looking up the data on imports of corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and rice by the each of the six countries for 1996 through 2000. The six countries import significant amounts of rice (11 percent of total world rice exports) and wheat (9 percent of total world wheat exports). They import very little corn, soybeans and soybean meal and virtually no cotton. Of the six, Cuba is by far the largest rice importer while Iran and Iraq import the bulk of the wheat.

The next step in the analysis was to decide how much of those imports would have been captured by the U.S in the absence of trade sanctions. While we considered several alternatives, I am going to report the results of the alternative with the most aggressive assumptions on U.S. exports to the six countries. For example, for the 1996 to 2000 analysis period, it was assumed that all the relatively small corn and soybean imports of the six countries came from the U.S., all Cuban rice imports came from the U.S. and the U.S.’s share of wheat exports to the six countries amounted to double our share of world wheat exports to the rest of the world.

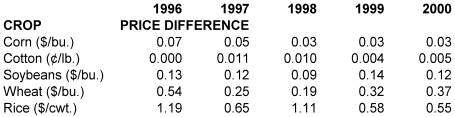

Table 1 shows our model’s estimates of the changes in prices resulting from these generous export share assumptions. The most important things to notice are a) that rice and wheat show the largest price increases because their exports increased the most and b) that the price increases tend to decline in size over the four years. As time goes along, farmers allocate more acres to rice and wheat and less to soybeans, corn and cotton, moderating the impact of the one-time sustained increase in crop exports on wheat and rice prices, and also increasing the prices of other crops.

Table 1. 1996-2000 estimated price changes for five crops resulting from lifting unilateral trade sanctions, using optimistic assumptions on U.S. market share of crops exported to these countries.

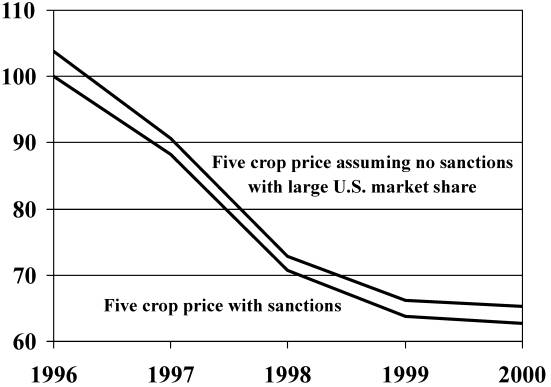

Figure 1 provides another view of the effect on the prices of the five crops of repealing sanctions on the six countries. All prices are indexed to their corresponding actual 1996 price levels. Removing the sanctions results in a one-time, permanent, rightward shift in the demand for crops. Thus, the greatest impact of the new export markets on crop prices occurs the first year when the index increases by 3.88 points. After the first year, assuming there are no additional countries from which to tap new exports, the price impact dampens as farmers respond to changes in the price of one crop compared to the price of another by altering the mix of planted acreages. With complete planting flexibility courtesy of the 1996 Farm Bill, changes in crop mix can occur quickly so that in 2000 the indexed gain is only 2.49 points. Overall, under very optimistic market share assumptions, if sanctions were lifted, the composite price of the five crops would drop by 35% instead of 37%.

Figure 1. Indices of five crop prices with and without the imposition of trade sanctions.

So in a qualitative sense, we can say rice and wheat farmers could benefit from repealing the sanctions. In our study, while the repeal of sanctions improves wheat and rice prices, they each still experience a 34% price drop between 1996 and 2000. This compares to about 40 percent price declines for each with the sanctions in place. It should be kept in mind that the price increases discussed are top-end estimates not only because of the generous export share assumptions, but also because the increases in U.S. exports are export reductions for other suppliers thereby exerting a measure of offsetting downward pressure on U.S. prices via international markets. The index of prices for the five crops increases only slightly. While, in my opinion, removing sanctions is a good idea and would benefit agriculture, their removal would not solve crop agriculture’s price and income problems.

Daryll E. Ray holds the Blasingame Chair of Excellence in Agricultural Policy, Institute of Agriculture, University of Tennessee, and is the Director of the UT’s Agricultural Policy Analysis Center. (865) 974-7407; Fax: (865) 974-7298; E-mail: dray@utk.edu: Web Address: http://agpolicy.org .

Reproduction Permission Granted with

1) Full attribution to Daryll E. Ray and the Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN;

2) An email sent to hdschaffer@utk.edu indicating how often you intend on running Dr. Ray’s column and your total circulation. Also, please send one copy of the first issue with Dr. Ray’s column in it to Harwood Schaffer, Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, 310 Morgan Hall, Knoxville, TN 37996-0001.