December 8, 2000

Quest for the Holy Grail of Accelerating Exports: Can it be found in China?

John Schnittker, long-time policy analyst and onetime Assistant Secretary of Agriculture, has said that accelerating exports is crop agriculture’s Holy Grail. Oddly enough there is some logic to this contention. In Raider of Lost Arc fashion, accelerating exports are pursued vigorously, promise to be lucrative, and in the past have been snatched away just beyond our grasp.

Over the last century, accelerating crop exports occurred three times: once during each world war and during a portion of the 1970s and early 1980s. Inflation adjusted prices also increased and increased just long enough, especially on the third occasion, to convince many that a new era had arrived only to be disappointed a few years later.

The most recent venue for crop agriculture’s desperate search for accelerating exports must be China. It began in the mid-90s. China’s record corn imports in 1994, mostly from the U.S., and near double-digit growth in Gross Domestic Product set off a frenzy of optimistic grain import projections for China.

The idea was that as real income increased in China, over a billion Chinese would be shifting their diets away from cereal-based foods and toward more meat and poultry. China’s perceived options were to import more grain while they focused on expanding their poultry and hog industries or to import sufficient quantities of poultry and other livestock products to satisfy the increased demand. The consensus was that China would produce as much of its own meat as possible and import much of the grain and protein meal to feed the additional animals. Since most of the imports would be corn and since the U.S. is the dominant crop exporter, U.S. corn exports would soar.

During this time it was as though analysts were trying to out-do one another on the size of corn import projections for China. Mid-90s projections made by the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) of China’s corn imports were above projections of some but significantly below others.

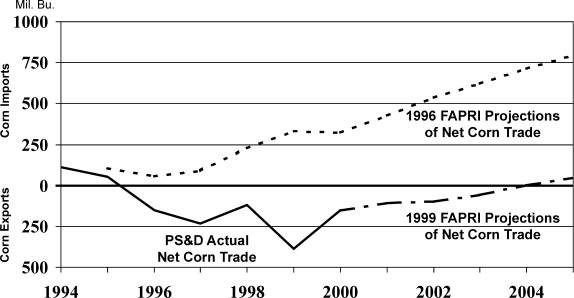

Figure 1 shows FAPRI’s December 1996 projections of China’s corn trade through crop year 2005 and compares it with actual Chinese net corn imports through crop year 2000 and FAPRI’s current-year projections of China’s imports from crop years 2001 through 2005. China’s net imports were projected in 1996 to reach 230 million bushels by 1999 and nearly 800 million bushels by 2005. The 800 million bushels of net imports would be equal to nearly half of the annual average U.S. corn exports during the 1990s. The bottom line on the graph shows that China actually exported more than it imported during the first five years of the period and is expected to continue to do so for most of the next five years.

Figure 1. Chinese Corn Trade¾A comparison of 1996 FAPRI projections with actual data for 1996-2000 and 1999 FAPRI projections for 2001 to 2005.

As optimistic as FAPRI’s 1996 projections were, even more optimistic estimates were bandied about at the time. Even analyses done by China’s Academy of Science and other Chinese research organizations differed only in the rate of growth of net import of grains, not the general pattern.

Based on actions taken, it seems clear that the Chinese government was certainly aware of the projected huge increases in corn imports and the increased claim on foreign exchange so implied. Beginning in 1996, the implementation of the Ninth Five Year plan placed great emphasis on agricultural development. An article on the China People’s Daily website says, “Since the launch of the Ninth Five-Year Plan in 1966, China has actively adapted its agriculture to changes in market demand and further optimized its agricultural services.”

Another force driving China to modernize its agricultural sector has been its 13-year goal of entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO). China has been well aware that entry into WTO will put great pressure on their agriculture. Chen Baodong, a researcher with the Guangda Securities Research Institute in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province says, “The entry [into WTO] will help China accelerate its agricultural reform and establish an agriculture macro-control system compatible with the market economy, thus enhancing the production of agricultural products and sharpening the competitive edge of China’s farm products in the international market.” China is looking to be a net exporter in the agricultural sector, not a net importer.

While intending to be a net exporter on average, unfavorable weather conditions will likely make China a net importer of grain in some years, not unlike the last four decades. What seems clear is that Indiana Jones is unlikely to find the crop agriculture’s Holy Grail in China anytime soon.

Daryll E. Ray holds the Blasingame Chair of Excellence in Agricultural Policy, Institute of Agriculture, University of Tennessee, and is the Director of the UT’s Agricultural Policy Analysis Center. (865) 974-7407; Fax: (865) 974-7298; dray@utk.edu; http://agpolicy.org/ .

Reproduction Permission Granted with

1) Full attribution to Daryll E. Ray and the Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN;

2) An email sent to hdschaffer@utk.edu indicating how often you intend on running Dr. Ray’s column and your total circulation. Also, please send one copy of the first issue with Dr. Ray’s column in it to Harwood Schaffer, Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, 310 Morgan Hall, Knoxville, TN 37996-4500.