January 25, 2002

What Have We Bought with Nearly $100 Billion?

It has become increasingly clear to me that our major corn and soybean export competitors will annually export whatever they produce beyond their domestic needs no matter what. It doesn’t matter much whether prices are “high” or “low”, whether exchange rates favor or do not favor our export competitors, whether inflation is raging or deflation has set in or whether we are or are not using annual set-asides in the U.S. Furthermore, we can find no evidence—beyond anecdotal hearsay—to suggest that changes in total crop acreage in our export competitor countries are affected significantly by any of these factors either. That is not to say that major-crop acreages have not changed, read increased, among our major export competitors. Those changes, long-term changes primarily, reflect the effects of developmental policies of various kinds, and not simply additional investments in agricultural infrastructure.

The country-by-country data are quite convincing. Annual soybean complex exports from Argentina are, for all practical purposes, equal to the amount Argentina produces less domestic use. Ditto for Brazil and ditto for corn exports from Argentina. Any production of corn and soybeans and soybean products not needed for consumption inside Argentina or Brazil high tails it out of the country. This ship-it-out-of-country-no matter-what stance means that year-end inventories following bumper soybean yields are about the same as year-end inventories during years when Argentina and Brazil experience a sharp drop in output per hectare.

While one is hard pressed to trace year-to-year fluctuations in Argentine and Brazilian soybean-complex (or corn) exports to variations in soybean/corn prices, currency exchange rates, or U.S. support prices and set aside levels, it is not that difficult to locate a pattern. Argentine exports tend to spike above trend when Argentine yields spike above trend; when yields are short, exports tend to be below trend.

The data are as unequivocal on the supply side. Acreages of our major export competitors appear totally oblivious to the factors that we economists, farm leaders and politicians have said are so important: prices, exchange rates, and U.S. policy. In fact, Argentina’s soybean acreage has been growing at an accelerated rate during these recent years of depressed commodity prices, no U.S. set asides and relatively “high” currency exchange rates for the U.S. and Argentina. Argentina’s currency tie to U.S. exchange rates, which has been in effect for a decade or so, was only severed a matter of weeks ago.

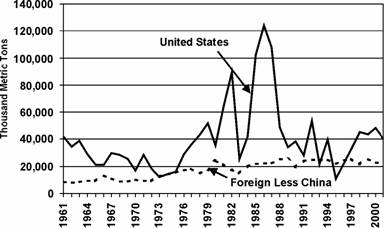

This discussion and the documenting data presented in earlier columns are based on country-by-country information. But what if we look at world-level data? Figure 1 shows corn year-end inventories for the U.S. and for the rest-of-the-world less China. China is excluded because it is difficult to verify Chinese data. The line representing ending stocks for foreign countries less China is relatively flat and steady while the line representing US carryover levels—well, it varies…widely.

Figure 1. A comparison of United States and foreign less China corn carryover levels, 1961-2001. Data source: USDA, PS&D.

During the 1991-2001 period, foreign-less-China ending stock levels of corn have been especially stable. During that time period, the carryover levels have varied from the 23.5 million metric ton level by ±25 freighter loads of corn while US carryover levels have varied from the 33.25 million metric ton level by ±267 freighter loads of corn. It is interesting that even in 1995 when crop prices were high and US carryover levels dropped to precariously low levels, foreign-less-China stock levels dropped very little. This all happened during a period in which foreign-less-China domestic demand grew by 14.4 percent or 609 freighter loads of corn. Next week we will look at similar data for soybeans.

So if the low prices and all-out-production of the last four years have not made the U.S. more “competitive” in the world markets, if it has not changed the behavior of our export competitors, and if it has not caused importers to increase their imports from the U.S. sufficiently to offset the lower prices, what have the tens of billions of dollars of government payments to replace market receipts lost to low prices and fence-row-to-fence-row production bought?

Daryll E. Ray holds the Blasingame Chair of Excellence in Agricultural Policy, Institute of Agriculture, University of Tennessee, and is the Director of the UT’s Agricultural Policy Analysis Center. (865) 974-7407; Fax: (865) 974-7298; dray@utk.edu; http://www.agpolicy.org.

Reproduction Permission Granted with:

1) Full attribution to Daryll E. Ray and the Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN;

2) An email sent to hdschaffer@utk.edu indicating how often you intend on running Dr. Ray’s column and your total circulation. Also, please send one copy of the first issue with Dr. Ray’s column in it to Harwood Schaffer, Agricultural Policy Analysis Center, 310 Morgan Hall, Knoxville, TN 37996-4500.